ADA @ 30: Two Voices on Accomplishments and Shortfalls

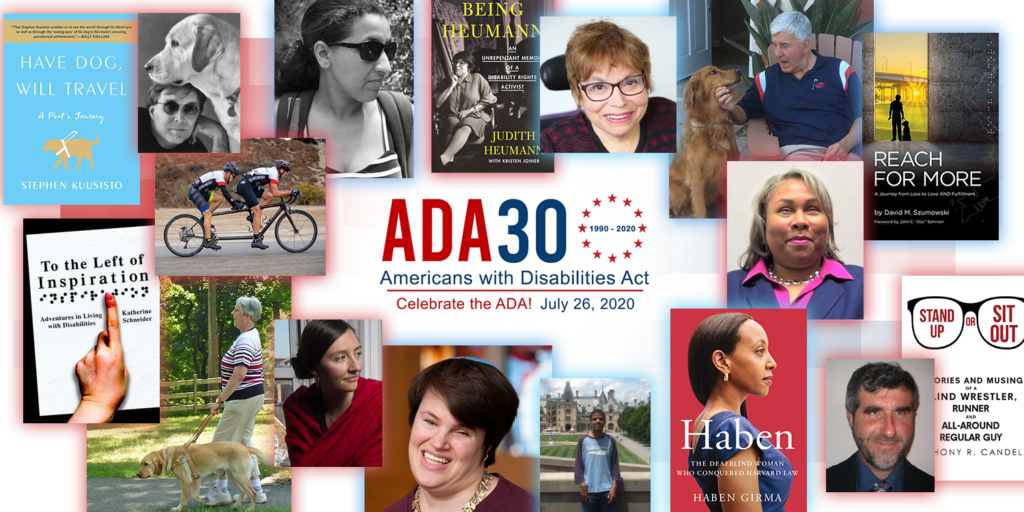

By Laura Deck, posted on July 28, 2020Disability rights activist Judy Heumann and author Stephen Kuusisto share their perspectives on the accomplishments of the ADA and the critical work still left to do.

Judy Heumann on Addressing Discrimination and the Importance of Universal Design to Benefit All

Before the Americans with Disabilities Act and Section 504, we were living in a society where trains, buses, and taxis were not accessible and captioning and sign language interpreters weren’t available. If you applied for a job and you were denied the job based on disability, you would not have protections unless a law in your state covered the private sector. We’ve come a long way, but there is so much work left to do.

It’s important for people to understand their rights and recognize and address discrimination. Sometimes it means filing a complaint, sometimes it means mediation, or sometimes it means having a discussion with an employer who is not willing to provide a reasonable accommodation. The government should invest in training programs similar to the ones held in 1990 just after the ADA was passed and the 504 regulations were signed. For many people it will be the first time that they learn about this legislation. Attendees can bring information back to their communities to ensure that the rights of people with disabilities are being upheld.

We also need to get the public to understand that changes made for disabled people are universal design issues that benefit everyone. We’ve seen this with captioning, audiobooks, smart speakers and the Kindle. The technology that drives these innovations came about to increase accessibility for people with disabilities, but many people just take it for granted that these features exist. It’s important that people understand that the advocacy of disabled people is not only benefiting those of us with disabilities but also the larger community.

Judy Heumann is an internationally recognized advocate for the rights of people with disabilities. Paralyzed from polio at eighteen months, she has fought for equality from a young age. She led the longest takeover of a governmental building in US history, resulting in the implementation of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, the first federal civil rights protection for people with disabilities. Her memoir is: Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist.

Stephen Kuusisto on Solving Albeism, the Dignity of Self-Advocacy, and Ringing the Doorbell Twice

I write as one who’s lived more than half his life before the ADA. As we celebrate its thirtieth anniversary, it may seem like the ADA has been around forever given how profoundly it’s shaped our collective understanding about disability and inclusion. For us older disabled there are some hard memories. I can remember quite clearly how lonely it was when insisting on my rights.

Why was it lonely? Because you had to invent your own accommodations and then insist upon them all by yourself. For old crips there was always that need, a desperation to figure out how to live. Life was a terrifying mathematics—an algebra—part hope, part reaction, part belief. We’ll get somewhere with this chalk. Then they came and took the chalk away. “Chalk just makes you more hopeful,” they’d say. Accordingly, old crips had to say, a la Samuel Beckett: “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

Now the chalk is a metaphor. Here’s where it comes from: in college when I tried to tape record lectures—you know, being blind—the professor told me I shouldn’t be in his class. Poof. The Dean didn’t care. It was a Kafka-esque world. That tape recorder just makes him more hopeful.

Tsk Tsk. Why is he trying to get an education at all?

Don’t get me wrong. These moments of ugliness happen post-ADA. Not long ago an autistic woman told me about how she was accosted in the middle of a lecture—in a big auditorium filled with students—for there was the professor standing before her and scolding her for wearing noise canceling headphones.

The difference, however, is that post-ADA the professor was informed by the university that he needed to apologize. Can an apology solve ableism? No. But it means at its core the disabled aren’t left to solve things on their own.

Moreover, the ADA gave the term self-advocacy true dignity.

It hasn’t changed the fact that the disabled are still not welcome at every party. It does mean you can ring the doorbell twice.

Stephen Kuusisto is the author of Have Dog, Will Travel; Planet of the Blind; and Eavesdropping: A Memoir of Blindness and Listening and several poetry collections. He teaches at Syracuse University where he holds a University Professorship in Disability Studies. He speaks widely on diversity, disability, education, and public policy. Read his collection of blogs on the ADA @ 30.

Learn how you can get involved in Benetech’s 30 for 30 campaign.

This blog is the second in a series of blogs highlighting perspectives from the Benetech community on the ADA. Read the first and third installments: “Together We’ll Rise” and ADA @ 30: Perspectives on the Past, Present, and Future